Archive for October, 2015

Protected: Ch-Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

Posted in Uncategorized with tags work on October 29, 2015 by sethdellingerwhere the light gets in

Posted in Memoir with tags central pennsylvania, dad, Erie, friends, harrisburg, high school, memoir, memory, mom, nature, pennsport, pennsylvania, philadelphia, prose, recovery, rehab, teen years, winter, woods on October 26, 2015 by sethdellinger1.

I awoke slowly, groggily, dry-mouthed. Beneath my body I could feel a bed, a nice bed, cushioney and soft, but also the obtuse crinkle of a plastic sheet. Then came the sensation of the plastic pillowcase; and then, finally, I remembered.

I was in rehab, and this was my first moment waking up there. I didn’t dare yet open my eyes. Who knew what kind of world this was?

My body felt sick, tired, disgusting. I was shaking, but not externally. My insides shook, as if my muscle and blood were a loosely-congealed jelly. I was hot–I could feel my body heat transferring from my head to the plastic pillow case. I had to cough, and vomit. Every bad thing a body can tell you, I was being told, but only slightly, moderately, on the periphery of emergency. I was in this facility for the treatment of alcohol dependency. I had arrived in an incredibly drunk state, and so only remembered small pieces of the event. I did not remember entering the room I was in, or laying on the bed. I had memory flashes of receptionists, bathrooms, swallowing pills. Bright fluorescent lights in drop ceilings. A hallway. Very little to go on. I had, in fact, no idea how long I’d been asleep.

I became aware of what had woken me: the sounds of people talking outside my room. Still without opening my eyes, I could tell these were people standing outdoors, by a window. As the crow flies, they must have only been seven or eight feet away from me, but of course, they were standing outside talking, while I was laying on a bed in a room with, presumably, the shades drawn. I felt badly the need to vomit.

With great trepidation I decided to open my eyes. I did so very slowly, not knowing if there might be someone else in this room with me, and if there was, I might want to continue feigning sleep. Gradually I let the light in–it hurt tremendously, giving me reason to think I’d slept for over a day. The room came into focus. Brown wood-grain particle board closets were directly in front of me, at the foot of my single bed. To my right, another single bed–blissfully unoccupied, the sheets and blanket meticulously made. A brown balsa wood desk in the corner to my left, and to the far right, a small door that looked like it lead to a bathroom, and beside that door, a larger door–this one presumably the door out. Probably to the hallway that existed in a flash somewhere in my memory.

The room looked frighteningly like any of the countless dorm rooms I’d lived and partied in only a year or two before, and only half a mile away. I’d lived in rooms just like this where the closet was full of empty beer cans and liquor bottles waiting for an opportunity to go out to the trash without getting caught. It did not seem that long ago that I’d looked at closet doors just like this one and contemplated hiding inside it, or peeing on it, or whatever. Now here I was in a similar but very different room. I was the same person I’d always been, nothing had changed inside me, but suddenly here I was waking up in rehab.

The sudden knowledge of the bathroom woke up a long-dormant pain in my bladder. With great achiness and slow care, I swung my feet out of the bed and limped my way to the small door I assumed to be the bathroom. I became aware that the entire place smelled of medicine, like an overly-air conditioned pharmacy. It was a sterile smell but reassuring; whatever was wrong with me, I was in a place to be fixed. Someday the shaking might stop.

The first thing I noticed was the sink. Not because there was anything very special about the sink itself, but because of the large red sticker attached to it, imploring residents to “wash thoroughly” in order to minimize the risk of transmitting Hepatitis. I peed into the pearly white, larger-than-expected toilet for what seemed like ten minutes. Relieved, I limped back out of the bathroom thinking I might sleep for another entire day.

But I became sidetracked on the way to the bed by the voices outside my window. Who were they? What was going on? I waddled to the window and ever-so-slightly pried open two slats of the industrial white venetian blinds.

Outside was a large courtyard, completely enclosed on all sides by the one-story brick building which I was inhabiting. The courtyard was large enough to house two or three full-sized trees, a gazebo, benches, and some concrete walkways. A dozen or so people were scattered throughout the courtyard, speaking in groups, smoking cigarettes, nursing tiny Styrofoam cups with steam rolling off the tops. They looked happy—almost like this was grade school recess or a break in a business meeting. They were of many different ages and seemed to run the gamut on the socio-economic spectrum. It looked like an inviting place to be, but also terrifying. I wanted to stay alone in this room forever. I wanted to get under the blanket where it was dark and plasticy and shake until the world ended, or my parents came and got me. Somewhere outside these walls my friends were going to work, stopping at gas stations, watching movies in living rooms. I could hear the chatter outside my window die down as the group was being called back inside. This was who I had become.

2.

Today I live about forty miles from the rehab I woke up in that day, which was over ten years ago. I live in an area roughly referred to as Central Pennsylvania, although some purists insist on calling it South Central Pennsylvania. Neither moniker is quite accurate, but anyway.

Most places in this world are the same, more or less, although cases for distinctions can certainly be made. Here in Central Pennsylvania, the case for distinction starts with the city of Harrisburg. Or, perhaps more aptly put, what the city used to be. A city on the rise throughout the 1800s, a series of events (both controllable and uncontrollable) caused the city to begin a constant descent into mediocrity and blight much like other, larger Northern “rust belt” cities from the 1920s until present day. Intense racial division, poor local leadership and the alluring habitability of rural areas outside the city caused an outward migration that has never fully stopped.

Harrisburg (and by extension, Central Pennsylvania) sits on the banks of the Susquehanna River. Although the Susquehanna appears at first glance to be a mighty, majestic river, it is in fact the longest river in the United States that is not deep enough to allow commercial boating traffic—another contributing factor to Harrisburg’s stagnation. The river at points nears a mile wide but is often shallow enough to walk the entire way across. Although it factors greatly in much of America’s history—the Revolution and the founding of Mormonism, for starters—its shallow depth prevents it from achieving any great level of fame, or any truly major cities from growing near it.

As citizens migrated outward from Harrisburg in the early 1920s they formed a network of small towns and communities so close together and homogenous that the ones on the opposite bank of the Susquehanna are often referred to simply as the “West Shore”, as though they were one community. These tiny towns, often quaint and artisan more than they were hardy and working-class, took their names equally from American history, Native Americans, and the local landscape. Towns like Camp Hill, Penbrook, Paxtang, Enola, Wormleysburg—each with its own identity, history, and geography, but each in turn also related to the exodus of Harrisburg. Camp Hill is named after a church whose congregation split into two groups—one of the “camps” held their worships on a nearby hill. Lemoyne—which used to be named Bridgeport—is a town of four thousand people that for some reason has an intense concentration of guitar and instrument stores. Paxtang is taken from “Peshtenk”, an English word which means “still waters”, although which still waters it was named for, we don’t know. New Cumberland hosts a notable apple fest each year despite being relatively far from where the apples grow. If one were to travel from each of these communities into the neighboring ones, you would notice small but not insignificant changes in elevation, a tangled network of water tributaries, bulbous outcroppings of sedimentary rock, and a collection of wildlife that includes the brown bear, the white tailed deer, the timber rattlesnake, and the turkey vulture.

All of these towns, and Harrisburg and the almost-mighty Susquehanna, are inside a valley. The Cumberland Valley is bounded by mountains from both the Appalachian and Blue Ridge ranges. All of the mountains are on the small side, as far as mountains go, although there are certain vistas that can be quite striking, especially in instances where the mountain ranges intersect with the river.

Although the Valley as we know it extends for only about seventy miles (and, at its narrowest, is only twelve miles wide) the Valley is part of a much larger geographic formation in the state of Pennsylvania known as a Ridge and Valley section, a land formation over a hundred miles wide that consists of repeating north-to-south peaks and valleys, formed, again, by the Appalachians and Blue Ridges. One can imagine (can one?) the difficulty these north-to-south peaks presented (and to a degree still present) to transportation efforts which in this state show a strong east-to-west desire.

In Pennsylvania, to the north of the Ridge and Valleys lies a vast expanse known as the Appalachian Plateau—basically a continually elevated area that looks like a mountain range but is really just high eroded sediment. This feature extends all the way to the top of the state until it drops off into Lake Erie.

To the south of our Cumberland Valley are the Triassic Lowlands—a small misnomer as there continue to be drastic changes in elevation throughout, but there is a distinct absence of mountains in this area, and most of the soil and structure is left over from the Triassic Period—some even from Pangea. The lowlands continue until Pennsylvania’s small Coastal Plain on the bank of the Delaware River—which supports commercial boating into Philadelphia.

However, this is how the modern human being would experience this world: be in your house. Travel a few feet out of your house into your car. Turn on your car, your air conditioning (or your heat) and drive to your destination away from your house. You will do this by navigating streets, interstates and intersections that you know by heart even though they have nothing to do with you or the land in which you live. Arrive at your destination. Walk a few feet from your car into your new destination. And this is how it is everywhere now—not just in Central Pennsylvania, but everywhere. You can move all over this country and most of the world and have a relatively changeless existence, never knowing where you are, what the place is like, what made it that way.

Sometimes our destination is in a whole separate town from where we started just a few minutes before, but the speed and ease with which we travel makes noticing these changes unnecessary. Sometimes we drive our cars over rivers and don’t notice. Sometimes we drive them through tunnels at the bottoms of mountains and bemoan the loss of cell phone service. Usually we don’t know the name of the mountain we drove under. We have no idea the struggle society went through to make such seamless east-to-west travel so unbearably easy. We see large birds gliding in circles, distant in the sky but don’t know what they are—we don’t even know that we could know what they are, that there was a time we would have known, would have been expected to know, would have been shamed by not knowing what the enormous graceful flying meat eaters were called. We’re unmoored, unhooked, disconnected, floating in a gel of inconsequence, we don’t know and we don’t know and we don’t know.

3.

My first year out of high school I went away to college–twenty minutes away. I went to a State School in the town next to us, and even though it was so close to home, my parents wanted me to live on campus so I would have the experience. I didn’t take well to the college experience at first (although later I would take to it much too well); I simply wasn’t making friends or doing the whole “college thing”. I was holing myself up in my room all week, ignoring everybody except the roommate I got stuck with, spending my nights on the phone with my girlfriend back home. On weekends, I went home and worked at McDonalds. And hung out with my real friends. And partied.

One weekend I was at a party at some kid’s parent’s house. I have no idea who the kid was, or any good recollection of who was there. I’m not even sure where it was, except that it was in a guest room above their garage. I spent much of the night at the far end of the rectangular room, beside the ping-pong table (it wasn’t in use; we were too lazy for Beer Pong) on old bench seats from the local Little League field after a dugout renovation some fifteen years prior. I was with three good friends who were still in high school, and we were ignoring most of the party.

Late into the evening, as most of the revelers had left and a dozen or so inebriated folks remained, an overweight, bearded man approached us from across the room. I had noticed him all night because he was so out of place. He was at least 28 years old, and a real Red State sort of guy. He wore a camouflage baseball cap and a red flannel shirt, and not the kind of flannel that was so popular in those days: this was the kind of flannel you wore so you could do physical labor in the cold, and it was really ugly. His voice was a thick drawl, thicker than a Pennsylvania redneck; this guy was from the South. This wasn’t a Redneck party, and it wasn’t a 28-year-old party either. In fact, it was a high school party. Even I was a little old for this party. This guy was a sore thumb.

He squeezed his way past the ping pong table and stood before us. I got ready to stand and shake his hand, introduce myself, ask him what the hell he was doing there. But before I could stand all the way he says this: “I know what you guys are.”

We all sort of chuckled, waiting for the punchline or explanation. One of us said, “What are we?”

“Fags. You’re fags, and I hate fags.”

This was shocking. It was shocking because, firstly, we were all raised rather liberal kids, by parents who thought just about everybody was OK and that everybody should be treated OK. Which is not to say that I never uttered the word fag, but we were all misguided youth who thought it was OK to slur if you didn’t mean it in your heart. And this guy obviously meant it in his heart, which was disturbing. Secondly, it shocked us because we were all rather straight, and anyone who had actually observed us throughout the party would have known that. Red Flannel’s statement clearly confused us.

We tried at first to convince him. The hostess of the party had slept with one of my friends, and an ex-girlfriend of mine was also present. We called them over to testify. But the more we tried to convince him, the angrier he got. He started to raise his voice, he started calling us more and varied names (it doesn’t take a genius, after the fact, to realize that this man was quite clearly struggling with his own hidden homosexuality, and his probable attraction to at least one of us. I wish I’d have realized it at the time; things may have ended differently). It didn’t take long for the remaining partiers to flock around us. The hostess and her friends stepped between the man and us. Of course, as soon as they took up that “we’re-stopping-a-fight” position, he took their cue and began to threaten all four of us with physical harm.

While it is true that this man could not have beaten up all four of us, he would have created one hell of a mess and more than a little pain by trying.

The ruckus lasted the better part of an hour, with Red Flannel screaming at us, everyone standing between us, the four of us on one side of the room bewildered. This variety of event didn’t happen to us. We didn’t get in fights, nor had we ever had to get out of a fight, and this made it difficult for us to remain the coolest cats in the room. It was too bizarre of a situation to know what to do. Everyone was now imploring the Red Flannel to leave. At one point, someone suggested that we leave, but Red Flannel made it clear that he would not let that happen.

Finally and somehow, the man left. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Some people laughed, some stalked around, pacing out their anger, muttering about how he had ruined an otherwise chill party. The hostess was afraid the neighbors had heard the noise and would tell the parents.

This idyll lasted only briefly, as perhaps ten minutes after he left, someone reported that he had pulled his truck up to the stairs leading down from the garage apartment–the only way out. His truck was idling. He had his parking lights on, and the glow of a cigarette could be seen behind the wheel. We let out a collective groan. We waited. Fifteen minutes later, he was still there. Our hostess was elected to go down and talk to him.

She returned moments later with the grim news: he wasn’t leaving until the fags left, and when the fags left, he was gonna kick the fag’s asses.

Suddenly and strangely the tone started to shift; although no one would say it, people were clearly beginning to resent us, and somehow blame us. With the Red Flannel no longer present to directly blame, the party was still ruined and there we were. We were quite clearly now blamed, having done absolutely nothing. Us “fags” sat ostracized in a corner while Hostess and Friends tried to figure out what to do. Do they call the cops? Do we wait it out? And somewhere in their subconscious–in that Lord of the Flies part of the brain–I know they had a third option: do we sacrifice them?

The uncertainty seemed to last forever, but in reality it was only about half an hour. The tension in the room was broken by a frightening smash, followed by even louder splintering and cracking noises. Everyone ran to the door, the gray dawn sky and birdsong of the morning shocking us all. And then even more shock, as we saw the Red Flannel’s taillights driving away, faster than a gunshot down the curvy country road, and directly below us the shattered remnants of the wooden steps leading down from the room we were in. He had smashed into them with his truck, rendering most of the lower half useless lumber, and severing the top half from its landing. The top half of the stairs now hung from the building by a few weakened planks, swinging slowly in decreasing circles.

Three days later, the property damage was listed officially as the work of a hit-and-run driver, who was never caught.

4.

A man turns a forty-year-old black plastic knob on his forty-year-old faded white kitchen stove in Pennsport, Philadelphia. Some mechanism inside the machine clicks repeatedly, while nothing appears to happen. Then suddenly a small, blue flame appears below the ancient burner plate. A man has turned a knob and a flame has quietly and simply come out of the machine. The man will put a metal pot overtop of the flame, add water to the pot as well as other human food products and create a meal suitable to his human palette, all made possible by that quiet little simple flame. For this service the man will pay about $30 a month, made out on paper checks and dropped in blue mailboxes. The man does all this, and eats his food, and pays the people for their services, but he has no idea what is happening, how any of it happens. In fact, he has such an absence of knowledge about it all, he doesn’t realize he knows next to nothing.

Outside the man’s house, if one were to travel mostly south, but a little east, for just a few miles—really just about a mile and a half, you would encounter Passyunk Avenue, a street that cuts unexpectedly diagonally across the city’s otherwise quite simple and helpful grid pattern. Turning left onto Passyunk Avenue, you would immediately be confronted by a large but not imposing bridge, what is known in bridge parlance as a double-leaf bascule bridge, which is fancy terminology for a drawbridge, but one that has two moveable sections instead of one. The Passyunk Avenue Bridge, as it is called, was completed in 1983 and is made almost entirely of steel and concrete, although the pedestrian walkways on either side have sections made of cast iron. The bridge crosses the Schuylkill River, the smaller of the two rivers that border Philadelphia, but alas, like even the smallest river, we still need a bridge to cross it. The Passyunk Avenue Bridge had to be built as a double-leaf bascule bridge to accommodate the heavy amount of shipping traffic that passes through the area due to the proximity of the Philadelphia Gas Works.

The Gas Works covers a sprawling hundred acres just outside of the city. This treeless, brown stretch of flatland right beside the Passyunk Avenue Bridge and sidling the muddy shores of the Schuylkill is a mostly ignored eyesore, one motorists tend to not notice that they don’t even notice it. The long wide expanse is brown dotted with yellows and reds, criss-crossed by pipes of all sizes, with seemingly-random outcroppings of unidentifiable structures, metal winged Eiffels growing out of the mud. The flat mechanical carnage stretches as far as the eye can see, until it hits the Philadelphia city skyline; a striking vista indeed.

Most of these multi-colored pipes contain natural gas, which in turn is a “fossil fuel”, which is exactly what it sounds like. Energy we obtain from extraordinarily old things, which in turn got their energy, during their day, from our sun, which is still around. We dig them up and squeeze our sun’s energy back out of them, thousands and thousands of years later. The Philadelphia Gas Works doesn’t talk much about where it gets its gas, but for the most part, it isn’t drilled here, although it certainly has been. Now it is mostly shipped here in those huge boats that go under the Passyunk Avenue Bridge. But see, here’s where it gets interesting: this energy from the sun was being stored in all these old plants and animals for eons under the ground. Then we found it (probably in what is known as the Marcellus Shale) and we went to great lengths to get it out of there. We’ve got to bust open the rocks that it is in, then we’ve got to shore up the cavity we created in the ground so that the gas stays there until we can get it. Then we have to remove all the impurities from it, so it can be used for things like cooking macaroni and cheese. These impurities include water; gotta get all the water and other gunk outta there. But see, if you’re trying to transport natural gas very far, it’s pretty inconvenient to do it in a gas form. If you can’t get it there in a pipeline (those pipelines only go so far) and you have to send it in, say, a boat, you have to now liquefy the gas. So we bust up the ground to get it out, then we turn it into liquid and put it in a boat. We do that by making the gas very cold. Now this boat chug-a-lugs down the Schuylkill to the Philadelphia Gas Works and huge pipes are hooked up to the belly of the boat and all the really cold liquid gas is pumped into huge tanks. Then there are other pipes that go from those huge tanks to what the Philadelphia Gas Works really are: the regasification plant. We warm it back up and make it a gas again. Then we shoot that gas out into a series of progressively smaller pipes that stretch out in grids that sometimes cover hundreds of miles, until they are in really little pipes that, believe it or not, are actually connected to your house! Then somebody who drops $30 checks into the mail every month decides they want to cook a stew, or maybe do some laundry. And miraculously, the little blue flame shoots out.

Now this man standing here in Pennsport, he doesn’t know any of this. And if you were to start telling him about it, he may interrupt you and ask you why it should matter to him. After all, he’s got his gas, he pays his bill, and everyone doesn’t have to know everything, right? That’s why there are specialists. But if you started asking him other questions, about other parts of the city and world around him, you and he might find he continues to know next to nothing about his environment.

Why are the sidewalks in his neighborhood a certain width? And different widths in other neighborhoods? Why are the blocks in his neighborhood so long? Why are they shorter elsewhere? How might these seemingly small details affect his quality of living? Ask this man what he knows about train traffic through the city, or the history of invasive plant species in Philadelphia. He doesn’t know, he doesn’t know, and he doesn’t care. He doesn’t see why he should. He is content to go to work and come back home and play with his things but the larger scope of the world and environment he lives in are completely lost to him; furthermore there is no compelling reason for him to change this.

This is the exact same thing that’s been said about kids in the country for a generation now, that they’ve lost touch with their environment. There isn’t that big of a difference between living in the country and living in the city. In rural areas people have become disconnected from the literal environment, in the cities it is our environment we’ve lost, but it’s all part of the same big moving parts.

In the country, there’s a difference between wildness and wilderness. Wilderness is what people settle for now when they think they are seeing nature. They walk on well-worn paths, drive their cars through parks, take tours. That’s wilderness, but there’s nothing wild about it. Wildness is self-willed, autonomous, self-organized. It is the opposite of controlled. It exists on all sorts of scales. You can see wildness in the movement of glaciers, or in the star-forming regions of the Orion Nebula. Wildness is everywhere. It starts with microscopic particles and it goes more than 13 billion light-years into the cosmos. It’s in the soil and in the air, it’s on our hands, in our immune systems, in our lungs. We breathe and wildness comes in—we can’t control it. And yet, nowadays, almost nobody wants anything to do with that aspect of the world, the real, the wild aspect. You can live in San Francisco, ride a Google bus to work, stare at a screen, come home, stare at a screen, repeat repeat repeat and never see an ounce of wildness at any scale, but do you know how close whales live to San Francisco? And giant Redwoods? There is wildness there to be seen, not just the microbes in your lungs, but at a scale that can impress a human, but still it is screen screen screen, nobody glancing around them. We are hive creatures now, far more so than in generations past, fiercely attached to our social network, which has become part of our identity. Nature is a movie that goes by outside the car window. And along with nature, the real world, the knowledge of the functions of the real world.

In the city, bureaucracy and layers of time and history stand in for the wildness that (only seemingly) gets lost in a metropolis. Instead of wondering about falcons and sediment layers we can instead pick apart the mystifying nature of zoning ordinances, inter-departmental transportation squabbles, and the righteousness of green space allocation. But we don’t, almost nobody does. So it is that no matter where we live, we’re just lost in a machine, or parts in a machine, not knowing what function we serve, not knowing where the machine is going, what we’re really doing. Turning on switches and turning knobs, putting on clothes we know nothing about to walk to stores we don’t remotely understand, living lives blindly, blindly, trusting in some overarching system to make sure we all get to some kind of finish line on time.

The man in Pennsport stands in front of his stove and makes a delicious meal overtop of his blue flame, eats it and loves it and gets a full belly while watching television, the screen’s glow not all that different from that blue flame, wherever it comes from.

5.

In the winter, Erie, Pennsylvania is a cold, desolate, sometimes dangerous place. It’s not the ideal place to live alone with no friends or relatives within a five-hour drive of you. It snows almost all the damn time, and it’s so cold, and the wind just races across the lake, whether it’s the summer or the winter. Whether the lake is frozen or open, it is seven miles wide, and there is nothing to stop the wind. On one particular winter morning, I rose to an early alarm clock, to work the morning shift at the restaurant where I was a manager. Our day started pretty early, and it’s always hard to get up, but especially when it’s dark outside, and the wind howls like a coyote, and you know there’s snow out there, and maybe more on the way, and maybe more falling even right then. I crawled out of bed, put on my work outfit, poked my head through the blinds, and started my car with my remote start, one of my most beloved modern amenities. Five minutes later I was down there to hop in, excited about the warm inside of my car. It had snowed the night before, but not a whole lot, maybe four or five inches, which isn’t very much when you’re living in Erie. But it was just one of those things, one of those moments where your car and the tires are sitting just right, or just wrong, and despite the fact that you see no perfect reason why, your car is stuck. I had not left myself a whole lot of extra time to get to work, and I was in quite a bind. Being late is sometimes easier than others in that line of work, and I can’t remember the circumstances now, but I do know that I absolutely had to be there on time that day, and my car being stuck put me in a moment of desperation. With nobody to call – not even any small friends or acquaintances, really nobody that I knew – I wasn’t sure how to proceed. I was out of my car, looking all around it, shoveling the snow out from the tires as best I could, trying to rock it a little bit. All the small things one can do by yourself to get your car unstuck, but there’s only so much of that. Then, in the predawn darkness I saw approaching a young man walking down the center of the street that I lived on. I recognized the speed with which he walked and the direction he was going as a man heading to catch a bus. Yes, there were buses, but I had never even looked into that. As he came to pass me I walked onto the street, and sent to him, “Hey man! Hi! Hey man, excuse me! I’m in a real bind here, my car is stuck and I really need to get to work. I’m really screwed here. Can you help me push it out?”

He stood still and wooden, looking at me through my pleading screed. After a pause, he said, “But, see, I’m on the way to catch my bus to go to work myself. What if this makes me late?”

This was one of those very touchy moments in life for me. I absolutely needed this guy to help me. But he had a point and I knew it. Why should he be late to work simply so I could be on time? I was sure if he helped me, the car could come out quickly and we’d both be on time, but time was crunched so badly, there wasn’t even the moment needed to explain this. I analyzed my chances, as well as the look of the kid, and rolled the dice. I said this:

“That’s a chance you’ll just have to take.”

6.

Sometimes when driving, or riding the train, or walking around in some park, I will try to get an image in my head of what the land around me would have looked like four hundred years ago. The same hills, the same landscape, but in my mind I’ll cover it in nothing and wonder what it was like to be the first person to chance upon it. This is always useless to me. There is so much wonder in this world, but I always have trouble getting past our influence, our disasters and clumsy systems. And even in those places where there is some real beauty, like over at Bartram’s Gardens, or up on Presque Isle, or down the road on the Appalachian Trail, all I have to do is take one look at the skyline in the distance, or the cement path I’m walking on, or hear the sound of the Honda hatchback blaring through the trees, and I am out of the tenuous illusion and coldly back in reality.

We are constantly tethered to some safety line. There is always a lantern, or a map, or a screen, or a cell phone. These things guarantee that whatever experience we’re having is just an attempt at connecting with something foreign and old, that it’s not real, no matter how real it looks. We’ve sketched out a new world over the old, and they are in two separate universes; the old is lost despite the remnants we see of it every day. If properly prepared, one could live entire decades indoors, in a world of their own creation.

Before I had a family I used to stay indoors for a day or two at a time, talking to no one and doing nothing of value. Once I did go outside after a long stretch like that, it still felt fake, like some slide in front of my eyes. At a certain point, I’d have to tell myself, This is actually real and I am actually here, that dog or building or mountain range in the distance is a real thing inhabiting the same space that I am. I think that must be a very modern sensation, that of having to convince oneself of reality.

7.

My father was born into orchard country. Nestled deep in the heart of Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley, near the intersection of the Appalachian Trail and the South Mountain. His youngest years were spent in rolling hills crowded by apple trees, which Mexican immigrants picked nearly year-round. There were Mexican restaurants around unassuming bends in the country roads; I never saw them but I can imagine they might have looked out of place, if one stopped to think about them. Dad told me a story once about a fancy-looking house that sat at the bottom of a gulley and was surrounded by Red Delicious trees. I saw the house myself—it’s still there. It looks like a small but stately plantation. When Dad was a boy, the house had an in-ground swimming pool, which was quite a luxury in those days, and they’d let him and his friends swim there occasionally. One Halloween, he was trick-or-treating and the family gave all the boys little pop guns—plastic guns that shot a cork out of a barrel. He thought they must be rich. He never forgot it. He remembers it like it was yesterday. My mother was born a mere 25 miles away, in a vanishingly small town surrounded by cow pastures, clumps of trees, and lean-to outbuildings. Farm country. In fact, she was born on a farm—a working farm, and she grew up doing the kinds of things you might imagine: collecting eggs from innocent chickens, watching her father and brothers shear sheep, waking up at the crack of dawn. Her dream as a little girl was to somehow, someway, move to the nearby small town and help her uncle run a pharmacy he owned there. She pictured herself sweeping the floor, stocking the shelves, maybe keeping the books. To her, this was a version of glamour. Her family would take in kids from “the city” who needed places to stay; Fresh Air Kids, they called them. Sometimes my mom’s country family swelled to great numbers; a surprising-looking bunch, I’m sure. My genes—whatever they are—are a swirl of them. I’ve got orchards in my blood, and my skeleton is a farm.

As a young child, I didn’t know much about my parents or where I’d come from. It wasn’t an issue I pondered. I knew that I certainly felt like me. I knew I liked to mostly not talk about what I felt inside. I knew I liked drawing things, and that I sure did love the outdoors. I liked playing with small boats in the bathtub, and Matchbox cars in the sandbox, and I hated going to sleep, and the dark scared me. There were two neighbors who lived two doors down from us—at the time it felt far away, but it is literally just thirty yards, I just looked at it not six months ago—who must have been 50 years old at the time. I considered them my best friends, although to them I must have seemed like a just occasional little person who happened by. I liked talking to them and imagining what their grown-up lives were like inside that big red brick house—what the kitchen looked like, what they ate for dinner. I miss them. They’re dead now.

I was a fairly typical teenager. I was mostly about having fun; everything was a joke. I could be cruel. I smoked a lot of cigarettes and experimented with just about anything that could be experimented with. I talked a lot. I thought I was important and smart. I hid secret desires and interests: poetry, philosophy, sexual confusion, the occult. I got angry, I got sad, I read classic science fiction novels late at night in my bedroom with the door locked. Women started to like me and it took me a long time to figure out what to do about it; when I did figure it out I tried very hard to be a “good guy” but still…I often failed. I liked comic books, American Gladiators, and MTV. Late in my teens I discovered Tumbling Run, a long hiking trail in the nearby Appalachians that follows a truly adorable stream, which is a trickle at the trail head and as you climb higher becomes a rushing set of falls and deep, clear pools. I would hike it by myself, find perches away from the trail, pull out a notebook and write poems tailored after E.E. Cummings. They were full of angst and love and fear. I thought Tumbling Run would be like my Walden Pond, but mostly, I just forgot about it.

As a young man I encountered my problems: alcoholism and depression. But those weren’t the only defining elements of my life. As I moved into adulthood I moved away from American Gladiators and even further from the tiny boats in the bathtub. There were surface changes, like a deeper attraction to poetry and literature and “serious films”, but I changed for real, too. I got angry. Angry at everything. I became of a mind that to judge everyone as harshly and vocally as possible was actually a good trait to have. I smoked a lot of cigarettes, often two packs a day. I was still funny, but now with more sarcasm and less joy. I liked staying awake until the sunrise, never cleaning my car, and throbbing rock and roll. I hated being alive.

After young adulthood up until this moment (what we shall refer to as life) I’ve just kept on changing. There are always the obvious, cosmetic alterations: a sudden liking for big band music and Cary Grant films, corduroy jackets and Florsheim loafers, art museum memberships and mini-figurines of Felix Mendelssohn. But also sea changes, but so fast; one moment I don’t want to talk to people at all, the next I enjoy the communion of strangers. Seemingly one moment, an actual pastime of mine is driving my car through the country at night, the windows down, blasting music from my CD player, smoking cigarettes. A few nights ago I walked home through the city, listening to my music in my headphones, stopping to read the menu in a restaurant hoping there were vegetarian options. One moment I’m vehemently opposed to sports, the next I’m at an NFL game.

A month or so ago, I had breakfast with two of my oldest, dearest friends. They looked the same as they always had, as I’m sure I did, and the little dirt-hole diner we ate in was the same as always, and the streets and parking lots were the same as they always were, when I was spending all my days there. But having been largely gone from the area for five years, it all felt so different, so foreign. Was that actually me that had lived here, had called these places home, these friends familiar? Or was it a dream had by a being who calls himself me? After breakfast one of the friends was driving me to my dad’s house, and as I climbed in his car I was overcome with a strange sensation. When I settled into the passenger seat I realized this was the car of a very serious cigarette smoker; ashes, crumpled empty packs everywhere, the stale pall of smoke infusing the upholstery. And it looked like many cars I had in my day: old drink cups on the floor, change everywhere, ATM receipts and food wrappers. I wasn’t grossed out; I felt oddly at home. It had just been so long since that had been me. It was like time travel.

If I’m able to look directly at the thought long enough, it becomes very clear that the notion of me doesn’t exist. I’m a collection of moments, an intricate study in cause-and-effect. I am the orchard, and the farm, and the boats in the bathtub, and the throbbing rock and roll, and walking home through the city last night. I am time itself. I’m not me.

8.

Somewhere everywhere bakers are opening up their shops. The tall commercial ovens click on with whirrs of electricity and gas. The little rooms get stifling and smell of yeast and flour. Today will be a ten or twelve hour shift. They will sweat through their white aprons and go home to unread newspapers. In other cities police officers are rolling out of bed, pulling their crisp uniforms on, fastening the large utility belt in the darkness of their century-old foyer while their family sleeps. The sun peeks over the rooftops and flowers open their petals in their pots along the sides of buildings. Third graders are walking to school wearing raincoats and backpacks and talking about pop singers. They have cell phones and they look up videos as they walk. The sunlight touches their necks and their tiny hairs stand up but nobody notices. A woman who works in a city newsstand arrives to open for the day. She enters through a side door and is alone in the tiny building, darkened still except for a small crack in the still-unopened front window where the light gets in. After taking her coat off, she walks outside, fumbles with the frigid padlock until finally the metal window slides open. It’s the loudest noise on the street yet this morning. Dozens of people are stepping onto an escalator. They avoid eye contact, they look at their phones, they pretend to be in a hurry. They wait on platforms, in hangars, on benches, in bus shelters, lines for elevators, by curbs for cabs, people are waiting. A man alone in a movie theater remembers an ex-lover while watching the Coming Attractions. For a moment he can’t remember what movie he came to see. At a grocery store a woman tries to decide which peach is best for her to buy and in the process she ruins five peaches. Now she can’t even remember if she planned on buying peaches today, and for a moment she wonders how there are this many peaches in the grocery store in the middle of winter, and she tries to recall if she’s ever seen a peach tree, or picked a peach, but she can’t remember, can’t remember, and now she’s thinking of her son away in college but he doesn’t like peaches either. All everywhere people are stuck at traffic signals on streets they don’t know the names of. They pass the minutes listening to talk radio coming from signals they don’t understand, from places they’ve never been, spoken by people they’ll never know. Their internal combustion engines idle beneath them-the sparks and fuel commingling to create a low-key contained continuous explosion. The light turns green and they’re off again to someplace else. An elderly man on a scaffolding nestled against a house hammers nails into shingling, and he will do it all day, all day, and more tomorrow. Grown people are everywhere furiously scribbling notes and typing e-mails and hanging Post-Its and setting reminders—there are so many things to do and to say and remember. A family of four is selling fresh fish in tables filled with ice by the side of the street. The kids should be in school but nobody seems to notice or think to say anything. The fish’s eyes are glassy and fogged up but people still buy them anyway, will still cook and eat them anyway, these hundreds of miles from the ocean. Mail is dropped through slots in doors. Squirrels pause on telephone wires, turning nuts around rapidly in their tiny hands. Landline phones ring in empty rooms and the neighbors can hear it, they can hear it, but they just have to put up with it. Waterfalls just keep insistently sliding over the cliffs, pounding the complacent ground beneath them and digging deeper and deeper holes. Somewhere deep, magma moves, hisses, is still. The tectonic plates are pushing the ground under our feet up into new mountains right now, right now, as we get onto this escalator, it is happening, the earth is forming new things beneath us right now as we ride the escalator, looking at our phones, it always has been doing this and it won’t stop until the sun, dying, swallows the whole planet. But smile anyway, you damned fools, and feel the hairs on your neck stand up in the morning sun, because there is nothing else, nothing else at all.

You’re Not Connected

Posted in Uncategorized on October 24, 2015 by sethdellingerYou’re not connected. Or you’re probably not connected. You’re not connected to the world around you. The natural world where you live–the changes in elevation, the bodies of water (where they come from, where they go, what’s in them), the kinds of trees around you, the wildlife–what else lives where you live? What do they eat? How does the food chain work and what are the integral links in it that keep your local ecology chugging? You’re not connected to that–you’re probably not, anyway. Why were the roads built where they were built? That is something you should know. You drive on them. They take you everywhere you want to go (or everywhere you think you want to go). You are not connected to how the towns around you ended up being spaced the distance from one another that they are. There is a reason for that. The history of the place that you live, it is unique and alive and it shapes the way you live now. There are famous people from your town–they were born there and went and did amazing things and then they died. They probably loved the town you probably know nothing about. There are famous people buried in your town (or near it, probably). The place you live, at some point, played an important and vital and interesting role in our nation’s history (and hence the history of the world), but you’re not connected to that, are you? Maybe you are. Are you connected to the weather? Do you know why these puffy clouds are up there today, meandering around a sunny temperate sky? It’s affecting everything about your day today, but do you know how it works, why it is like this today but it was gray and wet two days ago? Are you connected to the world you are moving through? Do you know what the sunlight is that is hitting you, landing so gloriously on your face? Do you know how long it took to escape from the sun, how it moves, why it feels warm? You’re not connected to the light, are you? I know I’m not. I try to be but I’m not.

It’s hard to be connected, isn’t it? How do we do it, where do we start?

How You Can Tell You Are Being Controlled

Posted in Uncategorized with tags college, Magnolia, memoir on October 19, 2015 by sethdellingerI got booted, declared Mark as he abruptly walked through the door into our campus apartment. I nearly fell from my perch on the sofa; not because he had been booted, but simply because he had opened the door so abruptly, and as always, he was very loud. But I managed to play it cool and keep watching “Magnolia”. I was at the part where everybody sings the Aimee Mann song.

This was our apartment at Seavers Apartments, the place to live at Shippensburg University in the 1990s. Whereas the other dorm buildings were your typical high rises housing hundreds of tiny, identical rooms meant for two roommates each, Seavers was a more modern building that had the appearance of an actual apartment building. Each unit housed six students, in two bedrooms of three each, with a large central common room. Each bedroom had it’s own full bath–a huge change from the communal public showers of the standard dorm towers. Seavers was also (and this was huge) the only dorm with cable TV. This was the 90s. Things were different then. I remember when I still lived in the regular dorms, being invited to a gathering at Seavers to watch “ER”; it felt like going to the movies for free.

So Mark, one of our six in our apartment, had burst in claiming he had been booted. What this meant, of course, was that the campus police had had just about enough of giving him parking tickets and had decided to “boot” his car, which entails locking a bright orange apparatus onto one of your tires, making it impossible to drive. You have to go pay your tickets and then someone comes and takes the boot off your car and your car becomes yours again. I still find this to be questionably legal, but it’s something that happens everywhere.

This was bad news for Mark. He worked off-campus and needed his car to get there and back, but if he had money to pay his tickets, he would have already done so. Not that this wasn’t completely the result of his carelessness–it was, but none of us were diligent, willful people at that time in our lives. How we perceived the booting was, this was the system making things more difficult for us than it had to. The system was toying with us.

There were four or five of us in the apartment at the time–I can’t remember who or exactly how many. But I do know that Mark’s rage over his booting was intense and pointed enough to rouse all of us out of our various stupors, get us to put shoes or at least slippers on, and make the trek out of our apartment, up the small hill and staircase to the nearby resident parking lot to gaze upon the bright orange monstrosity that was now attached to the rear driver’s side tire of Mark’s car. I don’t remember what kind of car it was.

On our way up the hill we had pounded on the doors of some of our fellow Seavers residents (these were pre-cell phone days) and had gathered more people with us, so by the time we gathered around the car, we had a group of fifteen or so riled up college boys, all mad at the system and rallying behind Mark. We stood in a semi-circle around the car, shouting obscenities and slogans in the general direction of the campus police station. It was hot and we were starting to sweat and I know personally I was very thirsty. Suddenly somebody said something amazing:

Let’s take it off!

It had certainly never occurred to me and probably none of us there that such a thing might be possible. This was an apparatus employed by the authorities, the very point of which was that it was not removable. That was the singular reason for its existence. But once it was said aloud it seemed oddly inevitable that we would at least make the attempt to remove it.

Before there could be any discussion on the topic, half of the guys assembled (yes, they were all males) darted off in the direction of their apartments to locate some tools with which to undo the authority’s handiwork. I did not have tools but I ran to my apartment with a few of my roommates so I could get an ice cold Dr. Pepper out of the fridge. I was so thirsty!

When we reconvened at the car a few minutes later, the more mechanically-inclined of the group (which did not include me) huddled by the tire. It was an exciting venture, but not one I expected to succeed. You couldn’t REMOVE A BOOT, everyone knew that, but it was nice to be out of the apartment in the sunshine with a Dr. Pepper and engaged in some sort of mission against some sort of invisible foe.

Ten minutes passed, twenty minutes. Some of the less-interested guys wandered off, went back to their Super Nintendos. Every now and then I would poke my head into the work area by the tire–there was lots of futzing with screwdrivers and pliers. It just didn’t seem plausible.

But then suddenly I heard a gasp, then a clanging sound, and then a whoop. Improbably and amazingly, Mark stood up with the boot in his hands, then held it above his head. The bright orange of the object somehow seemed out of place with the scene, one of youth triumphing over authoritarian evil, but this color swinging around over Mark’s head seemed to indicate an innocence, a folly. Mark released a barbaric yawp, a howl that somehow included the words screw and parking authority all in the same syllable.

Mark started jogging with the boot still above his head, much like an Olympic athlete circles the stadium displaying their national flag. We trotted behind him, feeling victorious by proxy, probably imagining all the other Seavers residents were somehow looking out of their windows at that moment, cheering us on, telling us we had won for them, too!

We ran all the way around the Seavers building once, then stopped back at Mark’s car. The momentary thrill of the victory was subsiding. Mark stood holding the boot at this side, and we were silent. We all looked at each other as a wave of realization slowly came over the group, the true reality of the moment and the truth of life within any tightly-governed environment. I was the first one to say it out loud.

We have to put it back on.

My Life in the Church of Nobody

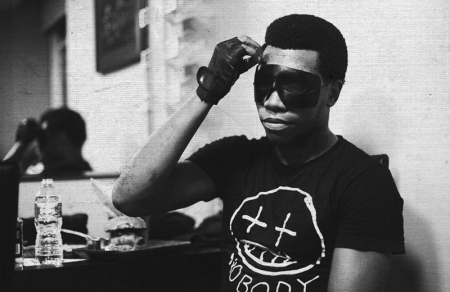

Posted in real life with tags concert, culture, harrisburg, music, pennsylvania, willis earl beal on October 16, 2015 by sethdellingerApproximately three years ago (the time period of my life when I was living with my mother in South Jersey), I was driving my car listening to NPR. I was listening to the show “All Songs Considered.” I had tuned in about halfway through, and was listening to a conversation with a musician whose name I never caught. He was a very serious man, he took his music very seriously and everything he said was heavy and dense, laden with meaning, a man many people might label as over-serious, and off-putting to some. But it was just the kind of talk I like, because I like art that is discussed with reverence. At the end, him and a small band played a song, the title of which I didn’t catch, although I caught some of the words. (it was “Nobody Knows”, although I have yet to find a recording of a live version that rivals the one I heard on NPR that day). The performance was absolutely haunting, and I couldn’t get it out of my head. Unfortunately, I had still never heard the man’s name, or even the name of the song. Eventually I Googled some of the lyrics, and I did manage to find out who he was: Willis Earl Beal. I YouTubed him, watched some performances, and fell quite in love. Not only was his music amazing, his lyrics were literature, and his voice had a bluesy-country-rock quality I’d never heard anywhere before; he sounded like God would sound if he was slightly drunk. But on top of all that he had a philosophy to his entire oeuvre, a philosophy of nothingness, of him being nothing, of channeling the universe, and all of us also being nothing. It’s a pretty intense philosophy, and more than I can really explain here in this blog, and maybe more than he could even explain to you, but something about it, somehow, connected deeply with me. I bought his debut album, Nobody Knows, on vinyl as well as CD, and even bought two extra copies on CD and sent to friends of mine who I thought might appreciate his music. I dove deeply into some of his online videos, they were not music performances but helped to fully flush out his philosophy, The Church of Nobody. It would be fair to say that for a short time at least, I was a disciple. Being interested as I am in tons of things, he slid off my radar a little bit after a few months, but would always pop back up here and there. I would say not two months will go by without me going to a small Willis Earl Beal phase.

Willis isn’t famous by almost any definition in America. You’ll never see him in a magazine, (although you might see his name briefly mentioned Rolling Stone). But there are a few circles in which he is very famous. Some of the alternative music press covers him extensively, treating him almost like the next Bob Dylan, with the positives and the negatives that might come from that. He appeared in the much lauded independent movie, to vehemently mixed reviews. Music and culture critics are very torn on how to take him and how serious he is, and his philosophical approach to music, which some say is absolutely brilliant, and some say means almost nothing. Following his debut album, Nobody Knows, he put out an album the next year, Experiments in Time, which I must admit even I was not a big fan of. It was too aimless and meandering, seemed thrown together in order to put an album out. It was also markedly different than the album prior, and if nothing else, I had to respect his change in direction.

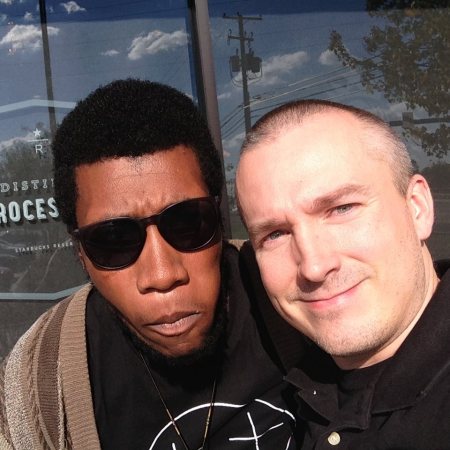

Flash forward to yesterday. I work at a nationally recognized coffee chain. I was sitting out in my lobby, doing some work on my laptop, when I looked up and saw what I thought at first was a kind of hapless man, walking around with a cell phone, looking for an outlet to plug it into so he could charge it. I had to snicker because of how fairly helpless he looked doing it, but there wasn’t much I could do to help him as none were open at the moment. I went back to my work. A few minutes later something caught me out of the corner of my eye. I looked up to see the same man, who was with a woman about his age, at one of my outside tables, apparently having trouble with a bee. He was trying to shoo it away from his table with a magazine. He was up and running around, and the woman he was with was laughing at him. I chuckled to myself, and then did a double take. The man was wearing a Willis Earl Beal T-shirt, that has his Nobody logo. My first initial thought was, holy cow, a Willis Earl Beal fan! It would have literally been the first time I had encountered such a thing. But then I realized the man I was looking at roughly matched Willis’ description. I looked at his face, and it was him! There was absolutely no denying it in my mind. Willis Earl Beal was at my place of employment. And before I knew it, I also realized that I was getting up to going talk to him. I can’t really describe the surreal nature of this, especially since I now work in a suburban Harrisburg, Pennsylvania store, not exactly the sort of place independent artists travel through frequently. But there was never a moment of hesitation in my mind, or any rehearsal of what to say, or even a moment of nervousness. I just said to myself, I’m gonna go talk to Willis Earl Beal . And that is what I did.

I walked out the front door, turned the corner, and cognizant of the fact that they might not want interrupted or bothered, I said, “I’m sorry, but are you Willis Earl Beal?” He definitely looked startled, as did the woman he was with, and he said, “yes I am!” The exact wording of what followed kind of escapes me. I thanked him for the music, and he expressed some shock that he had been recognized. Even though he is a large figure in some critical circles, he’s not a man who gets recognized often. We quickly began speaking very much like equals, like two people who were just talking to each other. It was one of the most surreal, electric experiences I’ve ever had. Now, while I’m a fan of Willis Earl Beal , I can’t say that he is absolutely one of my favorite musicians. That would be misrepresenting the case. He would not make my top 10. Would he make my top 20? Absolutely. I am passionate about a whole lot of things, and Willis Earl Beal certainly falls into that category. So all of a sudden, I go from working at my job in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to sitting across the table and speaking quite frankly and candidly to Willis Earl Beal. This is the sort of thing that simply does not happen.

After a few minutes I admitted I had not heard his latest album (Noctunes), and he offered to sell me a copy of it on vinyl out of his car. I quickly ran to the neighboring supermarket to get some cash, which I overpaid him for by a little bit in appreciation for his artistry. He signed the record for me, and him and his girlfriend (who is the woman he was with) did not appear to want to stop speaking to me. The three of us had a good rapport, so I just continued to sit there and talk to him. We spoke a lot about the nature of creating art, and how one’s voice and talent evolve over time, and how some of your earlier stuff can become unrecognizable to you. I told him about how I dabble in writing, and we spoke about that craft as well as the craft of music, me admitting I know nothing about creating music but my intense appreciation for it. We spoke about what it is like in our culture to become known like he is, but still struggle financially, and what is like to have people you don’t know recognize you, and how that changes you as a person. All in all, it was only a 20 minute conversation, but it was very real, and a very intense experience for me. I daresay in some ways it seemed to be a pretty intense experience for him too, not only to be recognized, but I think he rather enjoyed the conversation, as did his girlfriend,

I excused myself even though I had much more to say and didn’t necessarily have to get back to work, but I didn’t want to overstay my welcome. I went back to my laptop, and looked up periodically every few minutes, to the astonishing sight of Willis Earl Beal sitting outside the window. He was there for about another hour, when I watched him and his girlfriend walk off and get into his car. Another astonishing fact that came out of this meeting was the fact that he is playing a show here, in Harrisburg, tonight! How such a thing slid under my radar, I won’t know, but you best believe I will be there. I quite some time ago stopped hero worshiping people, thinking that the famous or semi famous people that create the things I love are somehow different or more elevated than me. So I definitely do not have a feeling that I was in the presence of a different sort of person in this experience, but the infinite level of statistical improbability of what happened, coupled with the ease with which the two of us fell into conversation, and the depth that we reached, cause a sensation in me but I don’t even have a word for.

Visiting Ado

Posted in Uncategorized with tags harrisburg, history, mail, postcard on October 1, 2015 by sethdellingerIt’s been awhile since I posted about old postcards, so for those of you new to my old bloggy-wog: one of the things I have an interest in is old postcards. I love them blank or with writing (they are two very different artifacts!). I adore finding collections of these in antique or specialty stores and spending hours poring over them.

Old postcards with writing are especially fascinating: they are glimpses into the past. The off-hand messages written by people (almost certainly now dead, written to people also now dead) who never expected long-distant strangers to be buying their postcards and reading the messages and pondering the lives of those in the past–it can often take my breath away. In addition, the evolution of the postal service (and by extension, our culture at large) can be traced via how the postcards are addressed, stamped, and postmarked. And the postcards themselves are beautiful and delightful artifacts, themselves changing in style and purpose about every two decades.

Anyway, I recently came across an enormous cache of old Harrisburg postcards at a local bookstore and my postcard interest has been renewed. I present to you here one that I just bought today.

This postcard is from the early 1930s. Almost anytime you see a postcard in this style–artist’s renderings in vibrant colors with a white border–they are from the ’30s. It shows what was then the Harrisburg Educational Building (now the State Archives):

The back, postmarked August 14th, 1933 (that’s 82 years ago, folks!) in Philadelphia, and sent to Marietta, PA (a town about 30 miles from Harrisburg). It is of interest that a Harrisburg postcard was sent from Philadelphia to a town near Harrisburg. Elements of the address are of interest. It was sent to:

Mrs. Frank Ziegler

Front St

Marietta Lanc Co

Penn

Of course the whole Mrs. Frank Ziegler isn’t surprising for the time, but given how the world has changed since then, it is of interest. The street address being simply Front St with no number speaks to a much simpler time, at least mail-wise, if nothing else. Note the absence of a zip code. The inclusion of the county was, I believe, even strange for the time period–I’ve never seen it before.

The text of the postcard is thus:

Monday, August 14, 1933

Dear Aunt Mabel

Dorothy and Marion are bringing Mother to Marietta to visit Mrs. Peck, so I decided since I wasn’t nursing I would like to bring Bob and myself along with them and stay all night with you then go to Quarryville on Thursday to visit Ado. That would mean four of us staying at your house Wednesday nite. [name I can’t read], Marion, Bob & I. Hope it is OK, See you Wed, Mimmie